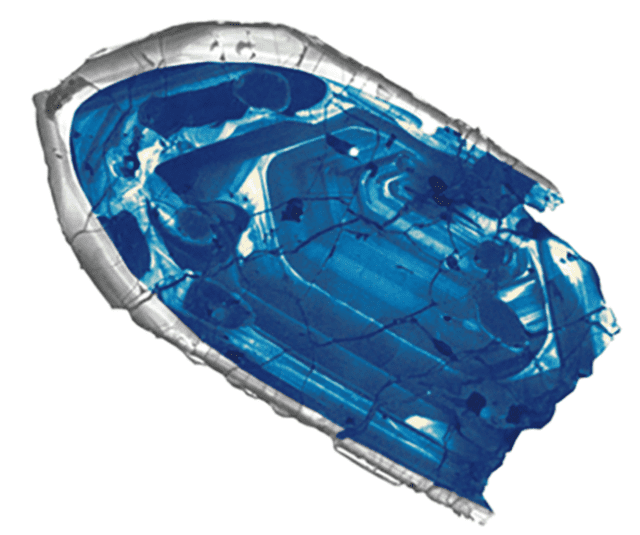

Scientists have discovered compelling evidence suggesting that Earth’s first rain fell as early as 4 billion years ago, much earlier than previously believed. Published in Nature Geoscience, the research reveals that the hydrological cycle—the process by which water moves between the atmosphere and the land—was active only 500 million years after Earth formed. By analyzing ancient zircon crystals from the Jack Hills in Australia, scientists detected unusually light oxygen isotopes within these minerals. These isotopes, typically associated with the interaction of water and rock deep below the Earth’s surface, indicate that meteoric water (water originating from precipitation) was present much earlier than once thought. This challenges the prevailing theory that Earth was completely covered by the ocean during this period and suggests that the planet may have had landmasses capable of supporting life much sooner.

The implications of this discovery are profound, as they provide new insights into Earth’s early history and the conditions necessary for life. The presence of rain 4 billion years ago implies that Earth had already cooled sufficiently to support liquid water on its surface, despite its fiery beginnings. This rapid cooling and the early existence of the water cycle would have created conditions conducive to the emergence of life within a relatively short time frame, less than 600 million years after the planet’s formation. As Dr. Hamed Gamaleldien and Dr. Hugo Olierook, the study’s authors, point out, this finding not only pushes back the timeline for Earth’s water cycle but also opens up new avenues for exploring how life on Earth began. The discovery underscores the importance of meteoric water in shaping the planet’s geology and, ultimately, its capacity to harbor life.