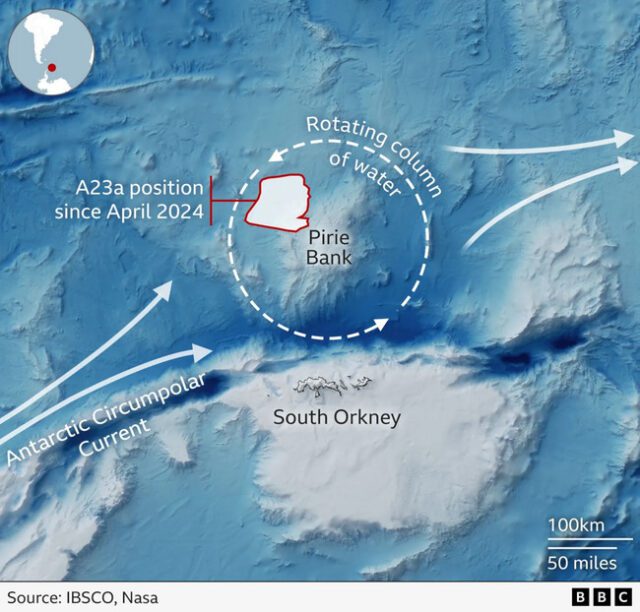

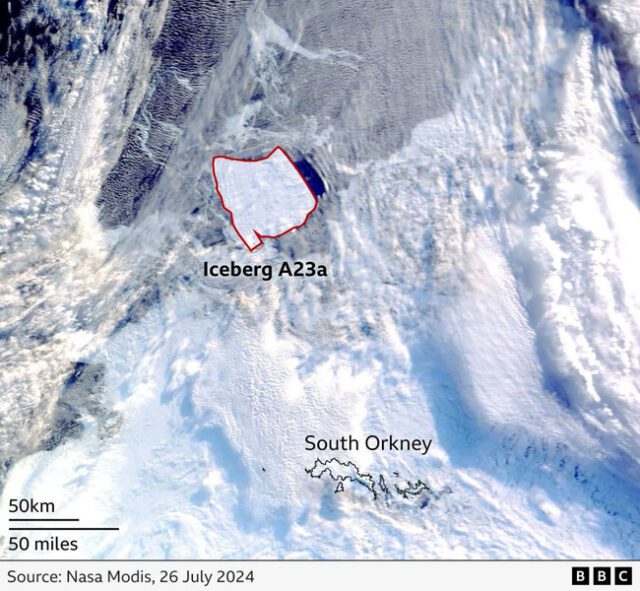

The world’s biggest iceberg, A23a, has been spinning in place north of Antarctica, contrary to expectations that it would be swiftly carried away by the powerful Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC). Instead of drifting towards its eventual dissolution in the warmer waters of the South Atlantic, A23a has been caught in a Taylor Column—a stationary, rotating water mass—created by an underwater obstruction called the Pirie Bank. This phenomenon, first described by physicist Sir G.I. Taylor in the 1920s, occurs when ocean currents meet seafloor obstructions, causing the water to split and form a vortex. As a result, A23a remains trapped, spinning anti-clockwise by about 15 degrees each day, which delays its decay and prolongs its existence.

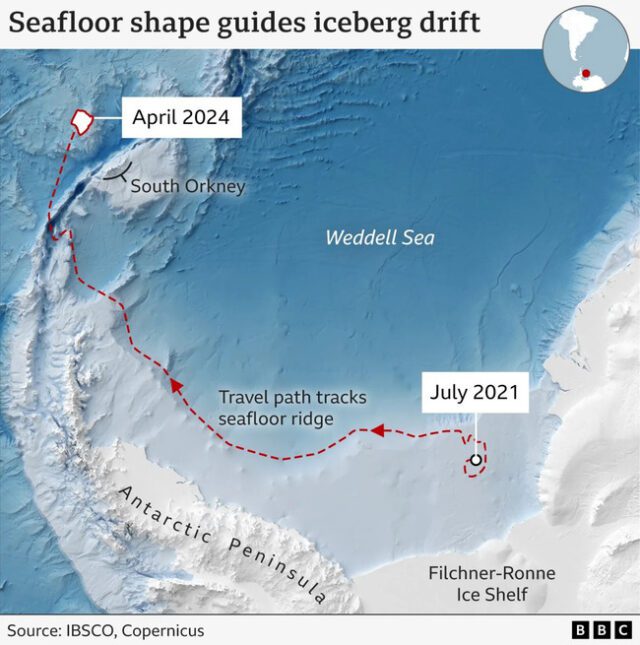

A23a’s remarkable journey and current predicament underscore the complex dynamics of ocean currents and the significant impact of seafloor topography on these processes. The iceberg, which broke free from Antarctica in 1986 and remained grounded in the Weddell Sea for three decades, only began moving again in 2020. Its entrapment in the Taylor Column demonstrates how submarine features like mountains and canyons can influence oceanic flow and biological activity by directing and mixing waters. This case highlights the importance of detailed seafloor mapping for understanding ocean behaviors and their broader implications for climate systems. As scientists continue to monitor A23a, its prolonged lifespan offers valuable insights into the interactions between ocean currents and seafloor structures, illustrating the unexpected ways nature can defy human predictions.